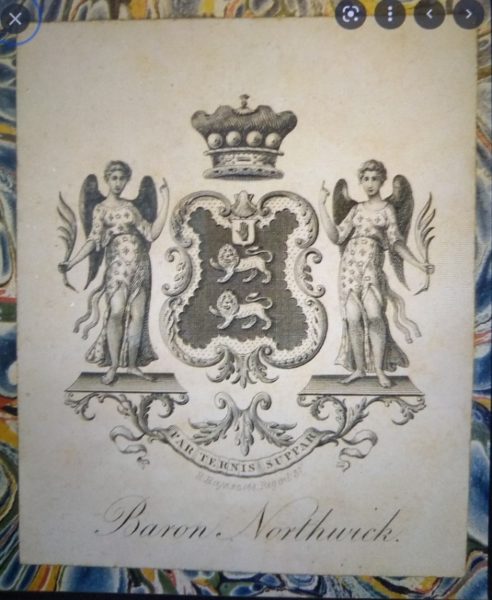

The Second Lord Northwick’s bookplate (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

I’ve always had a light, airy sort of desire for a bookplate but before ever thought became action, desire seemed to have dissolved away. A bookplate in today’s world seems a bit vain and self important and after all if you lend anybody a book the best thing you can do is just write your name in it (and, even more importantly make a note of to whom you’ve lent it … and the date lent is probably a good idea too). However, if you were Lord Northwick and had a library full of books hand bound in moroccan leather, a bookplate was undoubtedly an excellent idea, especially if along with your title comes a family crest just waiting for you to add your own individuating twiddles and flourishes. There is of course the further result – of no benefit to Lord Northwick at all – that when you die and your library is sold, books so embellished sell for oodles more than the equivalent unembellished – that little slip of pasted in paper providing just the sort of gold plated provenance second hand dealers drool over.

Book plate belonging to John Rushout, Second Lord Northwick

In pursuit of finding the exact origin of a well known story about a dinner in Lord Northwick’s Cheltenham house, I have been reading W.P.Frith’s Memoirs. Frith was a great painter of enormous canvases – you’ll probably recognise them when you see them – Derby Day (1856-7) Private View of the Royal Academy (1881), Paddington Station (1862) and The Marriage of their Royal Highnesses The Prince of Wales and The Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1863). Frith doesn’t always sound like a very nice man (and the anecdote I’m looking for show him not being very nice towards a fellow painter) but when he writes about the difficulty he has in trying to get sketches of both people and their clothes for his 10 footer picture of the royal wedding he has my complete sympathy and admiration. Although royal weddings are rather longer than ordinary ones, they are still very much too short for an artist’s sketching needs. Frith therefore had to ask guests to come to sit for him (bringing their dresses, dress uniforms, jewels, honours, orders, helmets sashes, etc). At first he forgot to say that the painting was painted for and by command of the queen; accordingly some answers came but there was mostly silence. An amended request was more successful – at least with the English. Foreign guests to the wedding, however, nearly had him beat, The Duchess of Brabant (later Queen of the Belgians) had worn a magnificent dress of moiré silk in purple (then a very new colour). A handsome woman, with a voluminous crinoline she had a prominent position at the front of the painting but both she and the dress had disappeared quickly after the wedding. Frith grieved over this with kindly Lady Augusta Bruce (afterwards wife of the Dean of Westminster) and she determined that as she was shortly to be going to Coburg, she would see what see could do. Lady Augusta was successful but only after getting the queen herself to intercede. The robes duly arrived but Frith had to swear neither to smoke nor drink beer when he had the mountainous silken confection before him. Then, Frith couldn’t get the Grecian king to come at all, so had to hijack his brother to sit for him when the latter came to visit Windsor. While Prince Frederick of Greece (or is it Denmark?) sat for Frith, the Crown Prince of Prussia came along to keep him company but when they came to leave the chamber neither would concede precedence to the other. In the end the Crown Prince backed out of the door while Prince Frederick followed, face to face. The next time they were to meet face to face was on opposite sides on one of the battlefields of Schleswig-Holstein!

Bookplate belonging to John Rushout, Second Lord Northwick

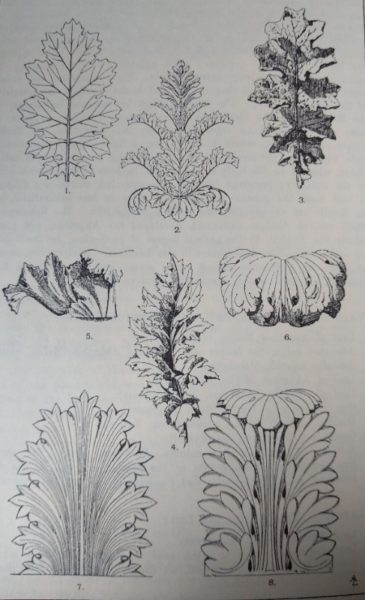

It seems that Lord Northwick had two bookplates. The one he used most and which probably superseded thee other slightly more crudely drawn version is the one I’ve had a go at copying. Interesting details to note:

The Baron’s coronet which has 6 pearls (some say silver balls).

Two angel supporters (seen since the C15th on the French kings’ coat of arms; the Rushout family – later the Lords Northwick – were Huguenots who came to England from Flanders in the C17th but it seems likely they were French originally.)

A shield with 2 lions (Interestingly the English king Henry I had a single lion and added a second when he married Adeliza of Louvain. Henry II the added a third lion when he married Eleanor of Aquitaine. Richard the Lionheart chose to keep the shield of 3 lions and of course it is these “3 lions on our shirts” which identify our national soccer teams. Confusingly, until the late C12th the animals were usually referred to as leopards!

The motto – Par Ternis Suppar: a pair is almost equal to three pairs – is either self evident or utterly inscrutable.

And tomorrow I shall be supporting the lionesses in their own quest for the European Football Cup. I’ve surprised myself by finding the women’s game fascinating – balletic, even elegant, pony tails flying and faces shining.