Ipsden altar frontal: the Thistle (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

For once, it is not my fault that I didn’t write a post last week. Nor was it the young master’s fault. The internet went down mid draft and after much fiddling on my husband’s part and much emailing and phoning on the son-in-law’s part, the delivery of a new but unnecessary hub and several vans and men in a hole in the pavement, normal service was resumed. So, here we are nearly a week later.

It is a relief to get back to thinking about flowers.

Now, no quilt of country flowers would be complete without a foxglove – and especially the common purply-pink one, Digitalis purpurea, which seeds itself in unexpected places when once admitted to the garden. In the past I’ve tried to grow white varieties or pale frilly pink ones but their seeds always reverted to the purply-pink ones, so I gave up and embraced what nature delivered. I dare say in Vita Sackville-West’s white garden at Sissinghurst (which has always had the most wonderful white foxgloves when I’ve visited), a team of gardeners sew tray loads of seed and hand pick the ones likely to be white – possibly an easier job than I thought as I’ve just remembered that Katherine Swift (The Morville Year p.75-6) does this all the time. Now to find the book….With it in my hands, I can tell you that when the foxglove’s basal rosette appears and is of a downy grey appearance, the flowers should be white, while a dark flush staining the midrib of the leaves indicates a coloured flower. Pity, now I know the technique, that too little time and the small matter of a lack of a garden of our own should be the limiting factors. Such is life.

Ipsden altar frontal, work in progress: foxglove (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

In the same book,Katherine Swift also points out that wild foxgloves, like the wild English bluebell, also have their bells all on the one side, which she rather likes – and so do I. (See illustration immediately below.) The hybrids with massed bells bunched up close to each other with not a centimetre of stem visible between them look too blousey and top heavy, especially when the little seed heads of the earlier bells have formed lower down and the bigger leaves at the base have started to go brown and get a bit shrivelled. (See last photograph in blog post.) Compared to these sturdy sentinels, the gently inclined heads of the single sided flowers manage to look more attractive even when past their best. Once again, less is more.

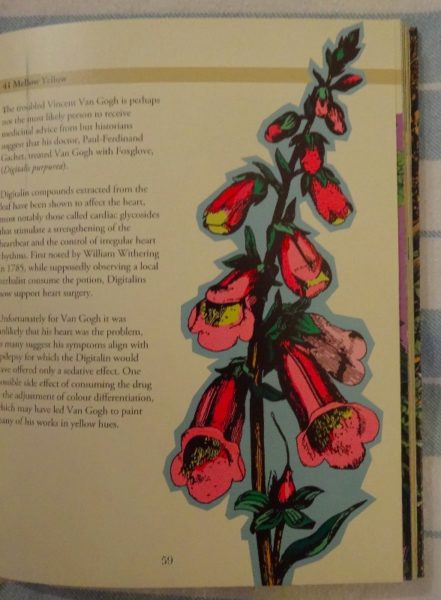

Foxglove illustration from ‘100 Plants that Almost Changed the World’ by Chris Beardshaw (pub.Papadakis 2013) Surely an English foxgove!

When I was young, my mother was always slightly neurotic if I came home with a bunch of wild flowers containing foxgloves for they were commonly known to be toxic, and had a bad reputation from incautious use in folk medicine. Much washing of hands ensued. In Richard Mabey’s “Flora Britannica” (so useful since found for a fiver in a charity shop) he recounts how a doctor, called to examine a herb-woman living in a wood in Repton found she had been treating herself with digitalis tea to combat breathlessness but had then moved on to eating the ‘tea leaves’ in sandwiches instead (presumably in this way taking in too much of the toxin, though Mabey disappoints by assuming the reader to have enough knowledge of plant toxicology to work out the moral of the tale for themselves.). I think I’ll stick to cucumber sandwiches from now on.

Ipsden altar frontal : foxglove (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Of course today digitalis has been tamed and is an important drug for the heart, whose beat it slows and strengthens. It also acts as a diuretic, supporting the kidneys to clear the body of excess fluid. Dropsy (accumulation of fluid in body tissues) was a terrible affliction and fortunately is an almost unheard of disease nowadays. In the late C18th, digitalis was used in its treatment but the results were unpredictable. Later in the century, physician and botanist, William Withering studied the plant, isolated the toxic part and quantified its effects to the point at which it became a useful medicine. Henry Fielding (1707-1754), author of “Tom Jones” and a sufferer of dropsy, was a bit too early to benefit from this knowledge and in “The Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon” describes in ghastly detail how the only alternative was purging or tapping, in which water was drawn off the body – up to 14 quarts at one time. Before he set off on his voyage he discovered that the lad serving as ship’s surgeon had never tapped for dropsy, so he called for a surgeon to tap him preventatively, and a mere 10 quarts was removed! Fielding did get to Lisbon but only survived a couple of months more – no wonder. Like Pepys and the removal of his bladder stone – WITHOUT ANASTHETIC – Fielding’s account of his operations is up there with the best of surprisingly horrible bits of literature that you don’t want to carry on reading but somehow just can’t bring yourself to stop. I’m longing to ask if anyone can think of any other literary horrors like these but then again I’m not sure I shall want to read the results. It’s one thing to be ambushed by unexpected surgery of a gory nature, it’s quite another thing to knowingly open a book with the sole purpose of reading such things.

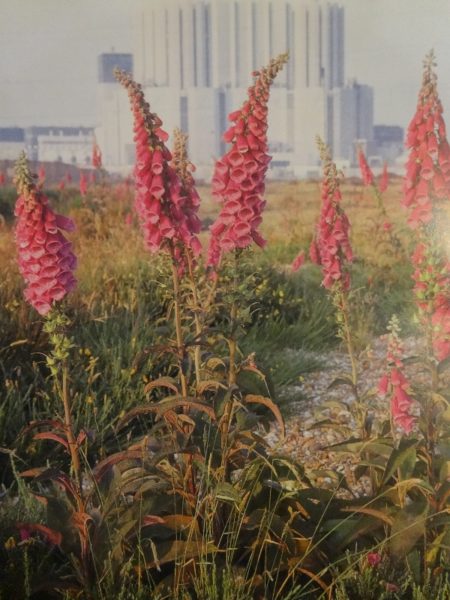

Foxgloves: Frontispiece photograph of Richard Mabey’s ‘Flora Britannica (pub. Sinclair-Stevenson, 1996). Not native English ones?

I managed a penultimate day visit to the V&A’s Opus Anglicanum exhibition last Saturday and hope to blog about this soon since – although the exhibition is over and thus unvisitable – the importance of the subject is much greater than you might imagine.