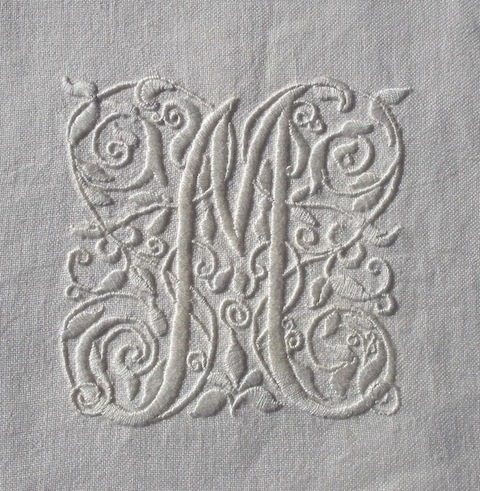

A few more flowers for the patchwork altar frontal.*

All three of these related plants grow happily locally and the violet in particular has made itself very at home around the large tree at the entrance to Ipsden churchyard. Both the violet (Viola reichenbachiana/ the early dog violet shown here) and heartsease (Viola tricolor) are true wild flowers while the multicoloured garden pansy (Viola tricolor var. hortensis) is the result of complex hybridisation involving at least 3 species in the section Melanium, one of which is the heartsease. Modern pansies are often distinctive for the well defined ‘blotch’, a spectacular black eye in the middle of the flower. There is also some difference in the way the petals point up or down. Pansies in the Viola sect. Melanium are supposed to have 4 petals pointing up and only one down whereas the violets in the Viola sect. Viola have 2 up and 3 down (error, err, artistic licence permitting). Botanical lesson over.

My mother’s name was Violet which I loved, although it was usually shortened to Vi which I wasn’t so keen on when I was little but which I’ve softened toward over the years – it now sounds quite dashingly innocent, like an Angela Brazil healthy hearty schoolgirl weaving her way up and down a netball or lacrosse pitch.

There have been some wonderful literary Violets.

There’s Violet Effingham in Anthony Trollope’s Phineas Finn. Orphan, heiress, beauty, she’s one of those excellent women (feisty and mischievous too) who turns down the hero, Phineas, and (finally) marries the rogue man she’s always loved. Miraculously – through the love of a good woman undoubtedly – her beloved settles down to become a good husband and an exemplary gentleman … oh and makes her Lady Chiltern into the bargain.

Still with the (fictional) aristocracy is Lady Violet Crawley, the Dowager Countess of Grantham, a redoubtable character whose sayings have spawned a Pinterest board solely in their honour (and thus Pinterest shows itself capable of being a sort of everyman’s Oxford Dictionary of Quotations). Of Branson, her grandson-in-law (and former chauffeur), she says, “If we can show the county that he can behave normally they will soon lose interest in him. And I shall make sure he behaves normally because I shall hold his hand on a radiator until he does.” Advice we may or may not want to follow.

Then who knew that Somerville and Ross – who jointly wrote those wonderful Irish RM books – when unpacked are revealed to be Edith Somerville and Violet Florence Martin, the latter writing under the name of Martin Ross? (Active as a contestant in our local village quiz league, I like to tuck these snippets back, though I can see that others may not find this interesting at all). Note to self to scour the library catalogue for the wonderfully funny and warm TV adaptation of the books shown on televison about 20 years ago.

Even more dashing was Violet Trefusis, lover of Vita Sackville West. Not only did their affair feature in their own fiction but it was borrowed by Virginia Woolf and used in her time travelling novel Orlando where, thinly disguised, the relationship achieved further notoriety. Nancy Mitford found Violet equally irresistible and based Lady Montdore on her in Love in a Cold Climate (one of those comfort books I slope off to the boudoir to re-read every so often when only a good laugh, a frothy capuccino and perhaps a few squares of dark milk chocolate will do.) More quiz fodder: Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall and wife of Prince Charles is Violet’s great-niece.

Sadly, Pansy has not had such an uplifting literary pedigree. I’ve recently re-read Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady about which I have completely changed my opinion. When I was younger I found the book, and especially Isabel Archer, interminably irritating and I have spent more than half a life time being rather rude about both the book and the main character. Age and experience have however left me better able to appreciate Isabel’s choices and her commitment to those choices. Particularly touching is her relationship with her young stepdaughter Pansy. Poor Pansy, a decent, docile, obedient daughter to the abominable Gilbert Osmond, has been drip fed lies since birth. When Isabel leaves Gilbert, she finds herself promising Pansy that she will return for her sake. This she does, though we aren’t really sure exactly why nor what her intentions are. Honourable enough to face up to her own mistakes and live with them, you can only be in awe of her – although you do find yourself hoping she’ll just grab Pansy and run back to England where she will not only face social censure full on but grab it by the ears and fight it to the ground. Hmmmmm.

Pansy O’Hara very nearly became a household name, but the Pansy bit was vetoed by the intervention of a canny publisher and Gone with the Wind appeared with the far better named Scarlett O’Hara instead. Just before publication, Margaret Mitchell upon being asked to make the change, wrote to a friend, ” We could call her Garbage O’Hara for all I care, I just want to finish this damn thing.” What a pity she didn’t make the book shorter while she was at it.

At 7a.m this morning I saw a thrush in the vicarage garden – the first for several years.

*For those coming to this website for the first time I should point out that these embroidered flowers are to be part of a patchwork altar frontal being made by the village for Ispden Church. Past posts on this project can be found in one of two ways :

1. Put “altar frontal” in the search box to the right of the main text and then click into each abbreviated text for the full entry. Please note that only 2 entries appear after the search and that after you’ve viewed these you need to scroll down past the two abbreviated entries and click into “older posts”. You will also find a few other altar frontals appearing by this method.

OR

2. Click into the Gallery and click into the relevant photographs as they appear if you want to read the accompanying text.

Sorry this is so long winded, I have yet to make time to index past posts.