I am still having problems accessing my photographs, so this post will be updated with more detailed pictures when I have solved the problem. I apologise for a post with rather a lot of text which I hope is not as boring as it looks. (14 August 2014: all photos added now and links checked.)

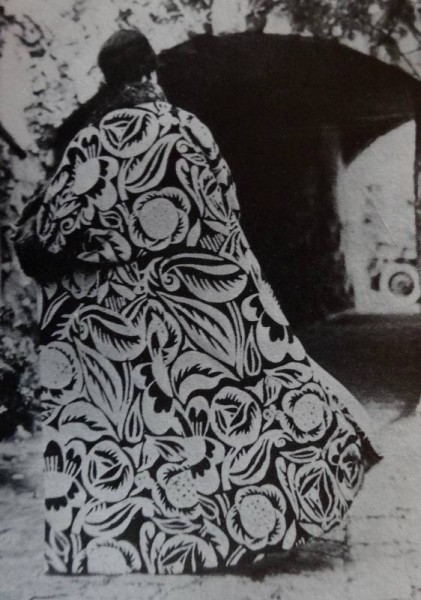

Sitting in Checkendon Church before evensong a few weeks ago my eye was drawn to a sculpted stone angel of downcast solemnity standing all of an arm’s length away in a niche on the north wall. Carved from a finely grained warm-toned stone its perfection is checked only by a single darker patch of stone on a wave of hair as it curves away from the middle of angel’s head. The pose and form of the figure hint – but do not shout – a female angel whose sleek fitting bias cut dress and slight silken belt suggest haute couture as much as anything else from on high. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Splendid hair cascades in well formed marcel waves in front of powerful wings, while at her feet stand plants (artichoke, bullrushes, sunflower & wheat) of sturdy muscularity, cousins to the 2 dimensional flowers of a Paul Poiret gown or Wiener Werkstatte prints.

Paul Poiret’s “La Perse” coat using Raoul Dufy’s fabric design (from Alan Powers: Modern Block Printed Textiles, Walker Books 1992)

Young owls, wings outstretched decorate the cushion capitals – that on the left is unfinished, but pitted to indicate cutting lines. In one hand the angel holds a long trumpet, but at rest it’s more like a staff than a musical instrument; in the other hand, a simple jug but whether for water of wine, I couldn’t tell – there seem to be no grapes among the fruit. A bit of a conundrum all told. There is little to be found written about this sculpture, except that it is in Hoptonwood stone and is known as the Rothbarth Memorial. The statue is arresting and, in a quiet way typical of the Arts and Crafts movement, stunning – I love it.

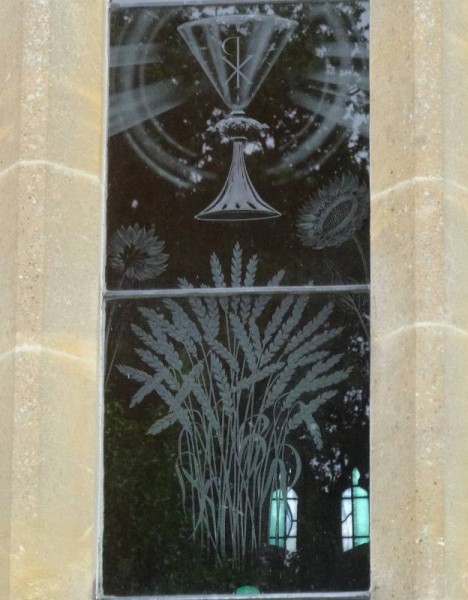

Everybody but me seemed to know that this little gem of sculpture was by Eric Kennington. I had heard mention of him mainly because of the window etched by Lawrence Whistler in memory of Kennington in the same church but I had been more interested in the Whistler bit that the Kennington connection. Now, my return home set me off in search of Eric Kennington and I discovered that not only was he remarkable for having been an official war artist during both world wars but also – perhaps even more remarkably – he had the bad fortune to end up being the most forgotten of all of them, in spite of being well thought of by contemporary artists and writers. (The painter William Nicholson admired and bought a pre-WWI work, The Costermongers with its echoes of Ford Maddox Brown’s painting Work, while the poet Lawrence Binyon in the New Statesman wrote that Mr Kennington “has a genius for reality”.)

Yesterday, as in churches up and down the land, we had special services in our 2 parish churches devoted to considering the start of the First World War and remembering the local families who lost their young men. Local war memorials commemorate a handful of names but as the years have advanced and more research has been done yet more names have come to light. Today, Ipsden and the surrounding hamlets probably have a population of somewhere around 300 (much less pre-1920 when you take into account the houses built since then); 16 men died. North Stoke has a population of just over 200 (again the pre-1920 would have been lower); 9 men died. Of those 25, there were 6 pairs of brothers.

Rothbarth Memorial by Eric Kennington in Checkendon Church: detail showing detail of unfinished owl capital

Eric Kennington lived locally in later life but was born in London and had lived there as a young man. Having a studio in Kensington – it is said round the corner from the local recruiting office – he joined up with the Kensington Battalion (the 13th Battalion, London Regiment, a territorial battalion). To begin with, in 1917, he drew what he saw of the war (soldiers preparing for war, practising with bayonets, bringing in prisoners, trying on gas masks and suffering from the effects of mustard gas) but after being invalided out (with trench fever and an amputated toe) he made a conscious decision not to depict directly the horror of the Front. His most famous work, The Kensingtons at Laventie, was painted in those early months in the battalion and is a group portrait of his comrades. Incredibly it was painted in reverse on glass and was much praised for its technical virtuosity, arresting colour scheme and the quiet heroism of the men. Measuring some 1600mm by 1800mm (5ft+ by just under 6ft) the mind boggles at how he carried such a thing around with him. Do read the blurb about the picture on the IWM’s site as it makes for fascinating reading.

Kennington returned to France as an official war artist just months after being invalided out and once again he worked quickly on whatever subjects came to hand – engineers in action, men suffering from the effect of mustard gas, portraits of men in snatched moments of repose, the changing landscapes. He was voracious in his appetite for subjects and begged to stay on when he was ordered back, saying that he had to ‘learn the war’.

Disliking being ordered about, he fell out with the Ministry of Information and, though still suffering ill, health joined up with the Canadian War Memorial Scheme for whom he went back out to France as a temporary first lieutenant attached to the Canadian Army. Work completed at this time was exhibited in Canada (40 + portraits and a larger painting The Conquerors ) and then in London where one of the last visitors before the exhibition closed was T.E.Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) who bought a couple of his drawings of soldiers. Though disenchanted with the British military establishment, Kennington let Lawrence persuade him to go out to the Middle East to draw portraits for Lawrence’s book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. (Interestingly Lawrence would never let Kennington use the portrait he did of Lawrence himself because he thought it was too revealing.) Kennington’s relationship with Lawrence was close and continued until the latter’s death in 1935 (at the funeral he was a pallbearer). Even after this Kennington and his wife were fierce defenders of his memory and when charges of homosexuality were made against their friend in a book by Richard Aldington, A biographical enquiry : Lawrence of Arabia they and a group of friends worked to try to stop publication. Aldington’s daughter later said that she thought they hounded her father to the point of near breakdown. Privately Kennington was pretty sure that Adlington had been right.

Checkendon church: Laurence Whistler engraved glass window commemorating Eric Kennington: detail showing wheatsheaf, sunflowers and chalice

After WWI Kennington experimented with stone carving. His first public commission still stands in Battersea Park, the war memorial to the 24th Division in Battersea Park (1924 -Robert Graves was the model for one of the 3 soldiers.) Other notable sculpture includes: a bronze bust of Lawrence (in St Paul’s Crypt), another bronze bust of Lawrence , the Soissons Memorial of 1929; 6 allegorical panels and other figures in carved brick on the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford and most famous of all the tomb effigy of Lawrence (1937-9) for St Martin’s Wareham.

Sir Kenneth Clark chose Kennington as one of the official war artists for WWII and once more Kennington entered a love/hate relationship with officialdom. In 1939 he went to Plymouth to paint portraits of the sailors who’d distinguished themselves in the Battle of the River Plate – frustration this time came through his perceived under use – he wanted more sitters than he was allocated. Next he threw his energies into the Home Guard and became in charge of 6 countrymen defending an observation post near Homer House, his home in Ipsden. There’s more than a whiff of ‘Dad’s Army’ here. He complained darkly that his men, ‘if not suitably motivated’ would appear for roll call of an evening and then slip off to go poaching, fishing or playing cards in the pub. I must ask around to see if anyone remembers him at this time.

But his reputation for bureaucratic obstreperousness was irrelevant to the public appreciation of his work and when the WAAC (the War Artists’ Advisory Committee) had an exhibition of official war art, his work, especially the portraits, was the most popular. The WAAC wanted him back at work and this time lured him with the bait of working with the one fighting service Kennington had yet to try – the Air Ministry. The Battle of Britain was at its height and portraits of allied air flight crew were required. Kennington was happy to do these (and they provide a unique record, especially because more than 40 of the men he drew were dead by the end of the war). However, when top brass began to outnumber ordinary airmen, Kennington again threatened resignation, which event was only just averted by a visit from the toppest of top brass, the Chief of Air Staff who talked him out of hasty action. (Though this was no doubt flattering, you can’t help but think the Chief of Air Staff had better things to be doing with his time.)

Some critics thought his portraits were of supermen, not mere mortal. The art critic of the Sunday Times thought their “assertiveness almost hurts the eyes”, although he did concede that they looked like men who would win the war, and even went on to suggest the portraits should be dropped as leaflets over enemy country and would be as effective as any bomb.

But would you believe it by 1942, Kennington was missing the army and the Army was equally missing Kennington skills as a portraitist, a painter of heroes, for this time his sitters were to be those credited with bravery in action, like those who came under fire in the retreat to Dunkirk.

1943 saw him back with the Home Guard when he was commissioned to raise their profile which had received a bruising from recent films, most notably, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. These paintings appeared in national magazines like The Illustrated London News, The Studio and Country Life to great public effect. It is interesting to note here that Kennington was a great admirer of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658, Lord Protector of England and signatory of King Charles I’s death warrant) and was among a handful of what we would now call the chattering classes, who considered Cromwell’s New Model Army to be an inspiration for the future development of the Home Guard. Possibly fortunately for Kennington, it was not historic Cromwell but literary John of Gaunt whose words accompanied his 1943 solo show at the Leicester Galleries. Two thirds of his portraits were of the Home Guard and the Sceptred Isle Speech (Richard II Act II, Scene I) hit the right patriotic note.

In later years Kennington settled down to live at Homer House, in Ipsden parish and he specialised in smallish memorials for individual churches (like the memorial in Checkendon Church), although his last known work (completed after his death by his assistant Eric Stanford) was a stone relief panel, The Progress of Science, (1957-8) for the James Watt (South) Building part of Glasgow University. He died in 1960.

I said at the beginning that Kennington was perhaps the least known of the war artists and I am glad that I have discovered that his reputation is undergoing something of a renaissance. Dr Jonathan Black of Kingston University has recorded an online lecture he gave, ‘Portraits like Bombs: Eric Kennington and the Second World War’ which is excellent. (Unfortunately many of the paintings he mentions cannot be shown for copyright reasons, which is a bit irritating.) He shows that Kennington’s special talent lay in depicting the serviceman as an individual, rather than making a painterly lecture on the horrors of war (which he had also done). Now perhaps with the distance of a century for WW1 and 70 years for WW2 it is the faces of those who fought that interest us once more and whereas black and white films and photos taken at the time made the world look very different from today, Kennington’s portraits of ordinary servicemen in the unexpected medium of soft pastels show the humanity of someone we might well think we’ve seen somewhere.

Update 14 August 2014

I begin to think that Kennington can’t possibly have carried a 6′ by 5′ pane of glass around the battlefields of WW1 and I can only claim that the following quote from Kennington on the Imperial War Museum’s website was a bit confusing.

The picture is a complex reverse painting on glass, where exterior layers of paint are applied first, giving the oils a particular clarity. Kennington painted this tribute to his comrades after he was invalided out of the army in 1915. He claimed he had ‘travelled some 500 miles while painting the picture on the back of the glass, dodging round to the front to see all was well.’

I now realise Kennington felt he had travelled some 500 miles dashing back and forth from front to back of the glass rather than travelling 500 miles marching through France. My mistake. Sorry, I must admit I’m rather unwilling to abandon my mental image of Kennington +pane of glass and multiple pots of paints trudging through the mud of northern France – shades of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and the hauling of a steamship from one river system to another and going up and down the mountain inbetween.

Anna Sander, Balliol College Archivist, comments below that she checked Ipsden on the 1911 census where a population of 652 was registered for Ipsden Parish (2001: just over 300). This figure caused much amazement at dinner locally the other evening and our ex-church warden * whose family have been here for 100 year + could only think that my husband was right when he pointed out how parish boundaries have changed since then. Yes, more people would have been crammed into farm cottages but surely not 300 more? Curious. This post and its update has exhausted me, so I shall leave it at this for the time being having abandoned a desired clarity of content for the mudiness of how things actually are.

*The father of the ex-church warden had been one of Kennington’s Ipsden Home Guards. No slur of sloping off to poach/fish/going to the pub, etc. should be attached to him – we think.