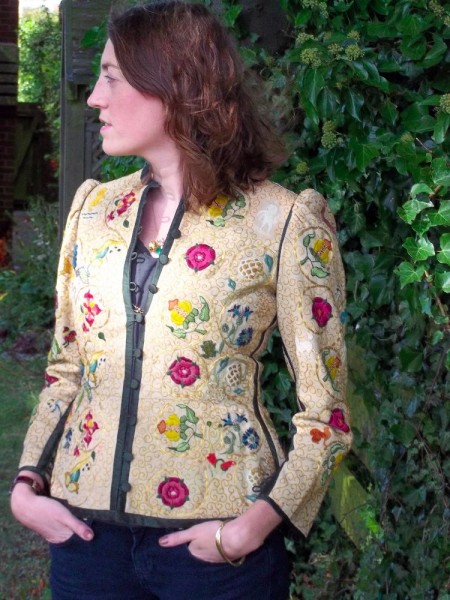

There’s something glorious about Elizabethan jackets with their profligacy of flowers and richness of colour through which rambling golden whirls of curlicues wander. I just had to make one. With all the enthusiasm of an 18 year-old whose A-levels were over and for whom an extended summer yawned empty until university in October, I began what was to become the jacket you see in the photograph above. The rest of the story is a bit of a let down as I have no memory of when I finished the jacket and I’m pretty sure I never wore it. However, in spite of never giving it an outing and disregarding all the things not quite right about it, I’m rather pleased at having made it. It is just a bit too tight for any of my daughters to wear for any length of time so I’m thinking of remaking it with a bit of extra fabric at the side seams. Funny thing is, considering the ornate clothing it would have been worn with in the late-C16th/early C17th, it looks really good with jeans. The other funny thing is that while I think of the style as Elizabethan, most of the examples you find date from after Elizabeth’s death in 1603. Thinking of it as a Jacobean jacket doesn’t sound at all right. Hey ho. (Google images of Elizabethan jackets and then Jacobean jackets and the same pictures appear.)

I can’t now find a picture of the particular Elizabethan jacket that struck such a chord in my teenage self and upon delving into the subject further I shall be amazed if I ever do find it, for somewhat surprisingly, there are about 50 paintings of proud ladies wearing such garments dating from this period – it was obviously a style in vogue for between 20-30 years, though whether I’m missing the fine changes to the style that would have updated the fashion, I can’t tell, particularly as so few of the jackets themselves have survived. (It is sad to discover that of those that have survived in museums their online details usually include the information that the jacket is in storage. Three of the best examples the V&A have all come with such a dispiriting addendum.) The Layton jacket – of which both jacket and painting survive and are on display in the V&A – is perhaps the best known example. Margaret Layton, a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth I, was painted by Marcus Gheeraerts (the younger) and she was married to the Master Yeoman of the Jewel House of the Tower of London. However, this wasn’t the jacket I remember looking at when I made my own. It is very lovely but I wanted to show different flowers. It may be that I just liked the swirlycue curlicues and went off and found flowers from different sources.

The origin of this particular stylised flora and fauna decoration in English clothing goes back to the mid- C16th century and coincides with the rise in interest in gardening and plant collecting. The first printed book of emblems was Italian and appeared in 1531. Herbals (illustrating flowers which had medicinal uses) and florilegia (which showed lovely plants at their most beautiful) became popular in England a little later. The first English emblem book was Geffrey Whitney’s (1586) which had 248 emblems, each entry consisting of a woodcut, a motto and a poem. Much of Whitney’s work incorporated material from the books of continental authorities and it was said to be from Whitney’s book that Shakespeare was introduced to the wider European literature on the subject. A frenchman, Jacques Le Moyne, published La Clef des Champs (also 1586) with the specific purpose that his prints of flowers should be used as a pattern book by craftsmen of all sorts. John Gerard, herbalist and gardener to Lord Burghley’s London garden in Long Acre, published his Herball or General Historie of Plants in 1597. Delightfully he often describes plants in terms of textiles. For example, of sunflowers he says, “the middle whereof is made of unshorn velvet or some curious cloth wrought with the needle”.

The golden scrollwork typically seen on the jackets was inherited from Opus Anglicanum, England’s famed ecclesiastical embroidery (which itself recalls Celtic ornamentation) and which is often still used today in ecclesiastical embroidery. My biggest failure on my jacket was not doing the scrollwork on an embroidery frame. My tension is wrong and the couched metal threads wander about all over the place like an abandoned set of railway lines. I don’t like using a hoop but it isn’t optional if you want to get metalwork to look good. When I joined the cathedral embroiderers, the first thing I had to do was set up a frame for a goldwork sampler. Once you have a frame set up, you have to continue with it and I wouldn’t have enjoyed sewing that way with wools. I like to feel the fabric and be closer to the thread. I suppose I could have done the flowers first and then put it on a frame, that would have worked better. But this is all the wisdom of hindsight.

This post shows just a few of the animals embroidered on my jacket. There are 6 unicorns (there may be more, I keep losing count and as I wonder whether I’ve counted the one tucked away by the underarm seam). I think I copied these mainly from pictures of The Lady with the Unicorn tapestries in the Musée de Cluny/Musée du Moyen-Age in Paris. In spite of having stayed for a week in a hotel on the same road as the museum, I never got round to seeing them – a ridiculous bit of carelessness.

My next blog post will show all the other animals and insects on the jacket and a further blog after that will have pictures of the flowers and discuss their symbolism. I suppose in consideration of how long it took to make the jacket, it is fitting to expend more than one post on it.