This third post on my Elizabethan jacket shows pictures of the embroidered animals and birds.

Outstanding embroidresses: Bess of Hardwick and Mary Queen of Scots

As you travel north on the M1, where the road slices through Derbyshire and nudges Nottinghamshire to the east, your eyes are caught by a splendid square built mansion that seems to grow right out of the crag on which it stands. On a sunny day, light reflects back from its massive windows as if calling, ‘look at me’, for this is Hardwick Hall, (“more glass than wall”), one of Britain’s least bashful buildings.

A prodigy palace, Hardwick Hall was one of a dozen or so extraordinary houses funded by the redirected wealth of the recently dissolved monasteries. If money had moved from the hands of the Church into the pockets of eminent families the least the latter could do was to make sure the monarch could be accommodated when progressing around the realm and these magnificent houses do indeed seem to have been built with the express purpose of being wonderful just in case the Queen of England should come to call on you bringing her court and all its associated paraphernalia. In the case of Hardwick Hall, it was the Grand Designs dream of Bess of Hardwick/The Countess of Salisbury, project manager par excellence, doyenne of Elizabethan interior designers and ultimately builder of dynasties. (Through her children she founded the Dukedoms of Devonshire, Portland and Newcastle and the Barons Waterpark.) Robert Smythson was the architect.

Bess was one of the three most fascinating women in the kingdom at this time and her fate was so intricately enmeshed in that of two other women that even now, 450 years later, it is difficult to unpick the knotted strands. At the apex of this triangle, of course, comes Queen Elizabeth I, lines of power emanating from her like some baroque statue of the Virgin Mary with gilded ormolu sunshine darting out from her fingertips, while another queen, Mary Queen of Scots /Mary Stuart, and Bess herself are caught in the angles at the base of the triangular composition, transfixed, eyes upward.

- Embroidered Elizabethan Jacket: budgie perhaps

Before I get completely tied up in my conceit, I should spell out the nub of the matter. Most of us have an inkling of the relationship between Elizabeth and Mary Stuart but it is often forgotten that the Countess of Shrewsbury was placed by Elizabeth in the unenviable position of the Scottish queen’s gaoler.

The whys and wherefores of Mary Stuart’s plight are not relevant to an embroidery blog. Suffice it to say that being a gaoler to one queen on behalf of another queen was a unique business and one that weighed heavy on the Earl of Shrewsbury’s already pinched purse. Both earl and countess expected their duties would not last long and they assumed they would be amply rewarded. In fact, Mary was with them for 15 years, resulting in tragedy for Shrewsbury. Financially ruined (though Bess herself wasn’t), he became strange if not actually mad, was involved in an unpleasant divorce from Bess and ultimately went to an early grave. That Bess was a clever woman who navigated her way skilfully through the Elizabethan inheritance laws and managed to keep her own money is another fascinating topic for consideration.

But back to embroidery, for out of this tragedy came some of England’s most splendid needlework. Both the imprisoned Mary and Bess were skilful and accomplished needlewomen and, fortunately for their confined lives, compulsive about it to the point of addiction. Brought together by serendipity, needlework was the bond that helped both to make the best of a dreadful situation. Between them (and 3 or so of Mary’s ladies) they produced a great deal of needlework, the most famous being the Oxburgh Hangings (1570-85), 4 in all (3 extant, one was cut up and used elsewhere), now on display at Oxburgh Hall in Norfolk. Each hanging consists of many motifs appliquéd on to a plain ground and each motif is usually made up of a bird/animal/figure in a shaped cartouche, sometimes with a name or a motto. These motifs were taken from the continental pattern books of the sort referred to in the previous blog post and were ones Mary had brought with her. Strictly speaking they are needlepoint, not tapestry at all, but as we know, from the Bayeux Tapestry onwards, tapestry has become something of a catch-all description for those who don’t sew.

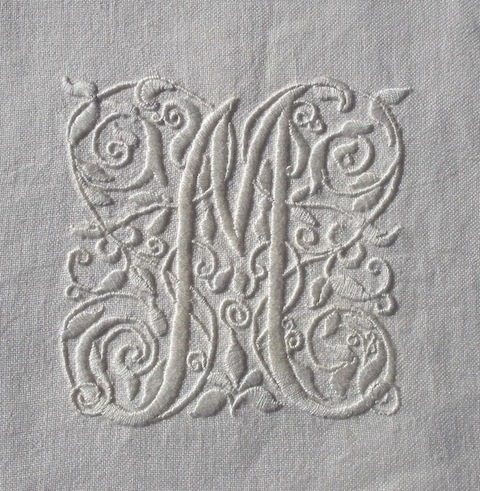

Not much of the needlework today seen at Hardwick was produced by the imprisoned women and their gaoler, after all Hardwick new hall was not begun until after Mary’s death. Bess’s meticulous account books show a great deal of money was spent on needlework supplies, but there were several other substantial homes requiring furnishing and she often employed professional embroiderers. When the present great cavern of a building was erected, it would have been easy for it to swallow miles of textiles, especially when you consider all those enormous draughty, flimsily curtained windows let alone the numbers of hangings needed for doorways, bed curtains, chair and seat covers, fashionable heavy tablecloths, ornamental hangings and coats-of-arms, etc. (Sometimes in the depths of winter, the temptation to tear down some beautiful hanging, roll it up and stuff it round an ill-fitting door must have been almost irresistable.) Certainly Bess’s initials ES appear everywhere, although as we know from written documentary details, when tapestries were bought from elsewhere they would have the former owner’s coat-of-arms unpicked and Bess’s added in their place. (One shopping spree after Shrewsbury’s death saw her buy 17 tapestries, including the Gideon tapestries, each of which underwent this treatment, although a recent writer of blogs, on visiting Hardwick Hall, describes the sewing of the monograms as being done very badly.)

- Embroidered Elizabethan Jacket: Stag

The most famous of Hardwick Hall’s needleworks on which the two women worked are the early panels the series of appliqués of famous, historical women, Queens Zenobia, Artemesia and Cleopatra (now lost) as well as Penelope and Lucretia (begun c.1573). Each of the historical figures stands framed by a Roman triumphal arch in a pose characteristic of her life accompanied by figures embodying associated virtues. Framing columns on either side have Ionic capitals because the Ionic style was thought to be more appropriate for the depiction of matrons rather than maidens. There are also mythical beasts, flowers, mottoes, coat-of-arms and heraldic devices (particularly the Cavendish stag and Talbot – Shrewsbury- hounds) and the twinned serpent design which Bess adopted. This first series of virtues was followed by another three hangings depicting Faith, Hope and Charity. Diplomatically, Queen Elizabeth is here embodied as Faith as she combats the Infidel. The symbolism in these works seems somewhat inconsistent and it may be that in these large decorative pieces int he final analysis meaning came secondary to concerns of interior decoration.

- Embroidered Elizabethan Jacket: jaunty goat

You can imagine why Mary’s work was full of symbolism, some of which was simple and easy to read to the point of being childish while other symbols were more subtle and complex, especially on items sent as presents to her supporters. But confidences were obviously shared over needlework and very personal symbolism then appears in some of Bess’s most intimate work as well. One panel has ciphers for the names of Barlow, Cavendish and St Loe (Bess’s 3 dead husbands) embroidered on to a pattern of tears falling on to quicklime (I haven’t seen this so I’m not sure how you depict quicklime…), the whole surmounded by a latin quotation which translated reads “Tears witness that the quenched flames live”. The phrase, used previously by the widowed Catherine de Medici, Mary’s first mother-in-law, seems likely to have been Mary’s idea. It also suggests that Bess had already made some sort of emotional break at least from her fourth husband, some years before their divorce.

What is not so clear is how much Bess knew of Mary’s secret letters, messages and plotting. Certainly both had reason to fear the other when their relationship deteriorated beyond redemption. As time went on it seems Mary learnt to play on the ever deepening division between her gaolers. While Shrewsbury softened towards her, Bess suspected this new intimacy indicated an affair. There is no evidence for this. Mary was removed from the Shrewsbury’s care in 1584 and it was under the new regime that she became involved in the plot that was to be her undoing. In 1586 Walsingham’s cunning plant to entrap her, known as the Babington Plot, came to fruition. What was different about this was that Mary had put in writing her assent to the assassination of Elizabeth and to the invasion of England by Spain. In 1586, an imminent invasion of England by Catholic Spain was a very real threat. She had gone too far but even then Elizabeth had to be pusuaded to the idea of putting another queen to death. Pragmatism prevailed. Shrewsbury himself told Mary of the death sentence on the night before the execution, the eve of February 8, 1587. Shrewsbury himself died in 1590. Bess began Hardwick (new) Hall in 1591.

Bess lived to be over 80, did not marry again and left her estate in good order. She died in 1608. It seemed that she wished the years of needlework not to be forgotten. A full inventory of the household furnishings of her 3 properties – Chatsworth, Hardwick and Chelsea was drawn up and in her will she bequeathed these items to her heirs to be preserved in perpetuity. The collection, known as the Hardwick Hall Textiles is the largest collection of tapestry, embroidery, canvas work, etc. to have been preserved by a single private family.

There are many books about Mary Queen of Scots but Antonia Fraser’s biography has lasted well. For more about Bess, Mary S.Lovell’s “Bess of Hardwick: First Lady of Chatsworth” , (Little Brown, 2005) is well researched and a good read.