Ipsden Church, Oxon: patchwork altar frontal, detail of snake’s head fritillary (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

The snake’s head fritillary is a particular favourite of mine. When I was an undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall (then one of only 5 women’s only Oxford colleges), the Librarian, Gisela Herwig, introduced me to sung Evensong at Magdalen College, performed with a full choir of men and boys every night during the 8 weeks of the university term. Though Magdalen and LMH were some distance apart by road, there was a direct, entirely green route through the Parks, via Mesopotamia (path between two stretches of water) and into Magdalen College grounds via Addison’s Walk. During early Trinity Term (the summer term), Magdalen water meadow would be full of snake’s head fritillaries. Though I didn’t realise at the time this is one of only 4 sites in England where they grow naturally in the wild. Sadly, that little slice of paradise walk is no longer to be had for free. The gate from the Parks into Addison’s Walk is now kept locked and today your rural walk has to be terminated here and calming greenery must be exchanged for the busy hubub of traffic on the Marston Road, the bustle of the Plain (a moderately attractive traffic roundabout – as roundabouts go) and the jostle of people pouring over Magdalen Bridge (with views of the Botanical Garden on the one side and Magdalen Meadow on the other) before you come to the college’s main gate and on to the chapel. Today you will be asked for a small fee to enter the college grounds, although if you want to attend a service in chapel, I believe entrance is free. After the service, I would return to LMH the way I came having had completely blissful couple of hours soaking up nature, beautiful architecture and the most divine music.

Ipsden Church, Oxon: patchwork altar frontal, detail of snake’s head fritillery (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

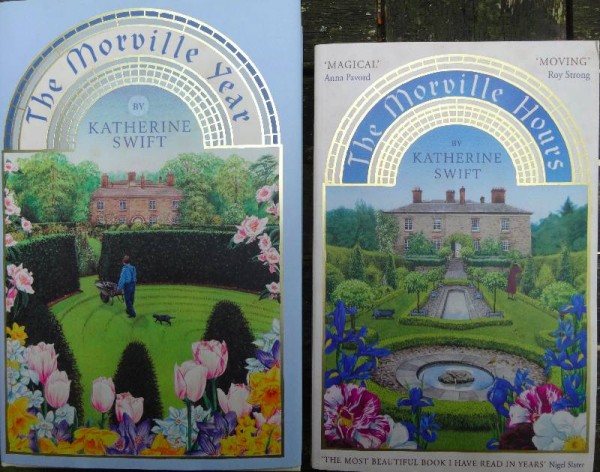

I turned to another librarian (well, former librarian) to learn more about the plant itself. Katherine Swift had a successful career as a rare book librarian in our own Bodleian Library and in Dublin when she decided that she wanted to create her own garden. This she set about doing in the grounds of the Dower House in Morville in Shropshire. For 4 years she wrote weekly columns in The Times which though ostensibly about gardening always contained so much more – including little un joined up snippets about her private life whose hinted intricacies became a source of regular fascination. When her 2 books on gardening at Morville came out, I rushed out to buy them, found them enjoyable and informative and placed them firmly on the list of ‘books to be given as presents’. Like Sir Roy Strong’s book on the Laskett, his garden in Herefordshire, Katherine takes us from virgin meadow to knot garden and so much more besides.

Katherine Swift: The Morville Hours (Bloomsbury, 2008); The Morville Year (Bloomsbury 2011)

In The Morville Year (Bloomsbury, 2011), Katherine traces the origin of the serpent part of the plant’s common name to the way the flower stem with its wedge shaped flower head uncoils as it grows upwards rather like a cobra rearing up in readiness to strike. The Elizabethan herbalist John Gerard thought it reminded him of the guinea fowl and called it ‘Ginny hen flower’ but Katherine finds such a name too tame for such a striking looking plant (she says malevolent looking but that seems a bit harsh). Fritillary flowers and fritillary butterflies are thought to derive their names from the latin Fritillus, a dice box (or perhaps the chequered games board) and it is true that flower and butterfly exhibit a sort of lozenge pattern of tiny alternating patches of 2 colours. In the butterfly this is brown and amber (visible as silver and amber on the under side of the wings), while Fritillaria meleagris have tessellations of ‘pale mulberry and sultry purple’ (Katherine Swift).

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Snake’s head fritillary (watercolour 1915)

Once abundant in the Thames Valley, the snake’s head fritillary’s decline is a marker for a dramatic change in farming practices. Since the war, 97% of our old fashioned hay meadows have become permanent pasture. The fritillary flourishes where a late summer hay crop is followed by grazing from Lammas Day (1 August) until Candlemas (early February). This light management gives the plants chance to grow, flower (early to mid April)and shed their fully ripened seed. But recent weather has been fickle and the fritillary’s hold in even these places has been even more tenuous. In 2012, Cricklade, one of the 4 major sites for the wild fritillary experienced severe flooding which meant there was no hay harvest. Instead the dead grass lay heavy and matted on the surface and impenetrable to the fritillaries so that less than 20% of the normal crop appeared in 2013. 2014 has thankfully seen a return to more prolific flowering.

Above is Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s delicate fritillary watercolour. Two weeks ago a disastrous fire broke out in the much loved Glasgow School of Art which he designed in its entirety from the granite exterior right down to the hand made fixtures and fittings. Let us hope that like the Cricklade fritillary the art school rises again to its full, albeit restored, glory.