I embroidered this dress in a style inspired by English smock embroidery but I have not used smocking in the sense of the sewing together of little pleats with honeycomb stitching. The traditional worker’s smock had far more embroidery than just that done on the gathered section of the back and front and it was this other embroidery that interested me at the time. I have done plenty of smocking itself on children’s dresses (of which more in future blogs) but here I was interested in the effect of concentric rings of chain stitch contrasted with light branching fronds of feather stitch. This was a winter christening dress for a summer baby (well, 2 summer babies, sister and brother, several years apart as it happens). The outer fabric is viyella (55% merino wool/45% cotton mix, in a twill weave) and it is lined with a fine silk and has a full underdress, also falling from the yoke, in the same silk. No baby wearing this dress would be cold, however draughty the church. The underskirt is edged in a narrow guipure lace while the outer skirt has a heavier lace in cotton crochet (added later). The whole thing was hand sewn as no sewing machine was available at the time. Hand washing has almost restored it to its former glory.

Christening dress in English smock embroidery: detail of yoke (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)It is interesting and instructive to consider the evolution of the word ‘smock’. In the middle ages it referred to a shirt or underdress; the outer garment that went over this was a ‘frock’. By the early C17th a smock or shift was a woman’s basic undergarment which acted as a barrier between the body and the outer garment. In theory it would be washed more often than the top garment and because of this it would be made of cotton in contrast to the wool or silk of the outer garment which was much more difficult to wash, or in the case of wool, to dry. By the end of the C18th the term smock was used less and shift used more, possibly because of various cultural/literary associations which had their roots in the C17th and early C18th centuries. The possible reasons for this are no doubt many but I quite fancy the influence of the two I mention below – maybe somewhat fancifully.

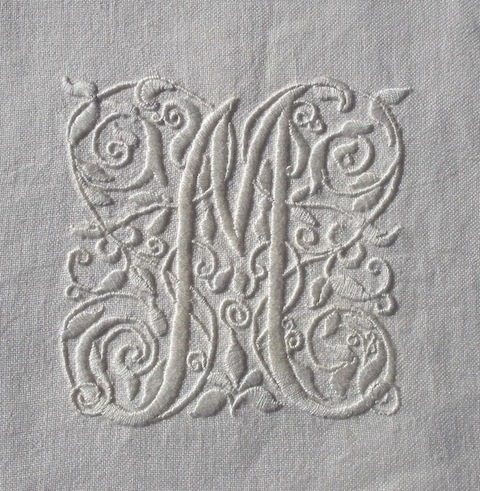

Christening dress with English smock embroidery: detail of back yoke (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Smock Alley Theatre, fronting on to the dirty street for which it was named, was Dublin’s first royal theatre built in 1662 after the restoration of the monarchy with Charles II’s succession to the throne. Thomas Brinsley Sheridan’s father was actor/manager of the theatre for some years and classic restoration comedies (like T.B. Sheridan’s ‘School for Scandal’ and Goldsmith’s ‘She Stoops to Conquer’) were performed. Most of these plays were full of crude inuendo and outright sexual misconduct much of which would amount to sexual harassment today. Yes, I know one cannot judge previous times by the mores of today but my only point here is that the degradation of the word ‘smock’ could well have been given bucket loads of help on the path towards gutter dwelling from the innocent word’s association with the rude, rather crude (and often very funny) plays that strutted their stuff at Smock Alley Theatre.

The sore having been rubbed to irritation in with coarse drama, it took the refinement of poetry’s sharp tool to deepen and infect the wound to death. In 1712, Alexander Pope wrote ‘The Rape of the Lock’, a comic, mock-heroic epic poem parodying ancient poems like the Iliad. In Pope’s poem, an almost inconsequential incident, the cutting off of a curl of the heroine’s hair, is treated with glorious hyperbole as if it were a crime as enormous and ramifying as the abduction of Helen of Troy in the Iliad. During the next few years various parodies of Pope’s poem emerged, one of which was Giles Jacob’s ‘The Rape of the Smock’ of 1717 in which his heroine, Celia, offers to trade the physical glories of her body in return for the retrieval of her most treasured, though presumably transiently fashionable possession – her smock – from the man who has stolen it from her. Not only is this a symbolic assault on Pope’s reputation but it is also an assault on the value that women place upon their bodies in comparison to their fashionable attire for which view, heaping insult upon misogeny, he is so brazen as to “request of his female audience that they forgive him”. See Deborah Laycock’s fascinating study (tantalisingly available in part on Google Books) here. Jacob followed this work with a piece of pornographic writing. Enough said. (How on earth did I get from christening gowns to sexual impropriety?)

Christening gown with old English smock embroidery.

(Hand embroidered by Mary Addison). I love this picture for the way the fullness of the fabric has be caught mid movement.

It should thus be no surprise that by the late C18th smock was scarcely a term to be used in polite company and that the more innocent term shift, no matter however many stitched gathers it boasted, should be preferred. (In the 1960s shift was the umbrella term for a straight, loose dress with a minimum or no gathers – think of those simple little Mary Quant dresses with nothing more than a couple of darts for shaping). In essence, the C18th shift clothed the nether regions during the day and doubled as sleepwear between the bedsheets at night. If you were poor, both functions would be served by the same garment.

Christening dress: seam neatening with buttonhole stitch – not so neat but necessary when no sewing machine is available

At about the same time as the shift went underground, so to speak, the smock became the dress of choice for the working man. The loose gathers gave facility of movement and a good sturdy linen would last many years. Sometimes embroidered panels exhibited patterns suggestive of the various trades. A wagoner or carter might have wheels (which is what I suppose that I have embroidered on the christening dress), while a shepherd might have patterns based on the curly end of a crook, the bars of hurdles/fences or sheep. Gardeners might have flowers, ranging from simple five-lobed shapes to more complicated arrangements of what look like orange segments, and there might be little triangular fir trees whose strong lines complemented the flowers; trees could also indicate a wood worker of various sorts. The Welsh were apparently very partial to hearts and tear drops. Few women wore such smocks and those that did seem to have been milkmaids for whom hearts (but not the tears) were also favoured. I’m sure the patterns/jobs relationship was nothing like as rigid as I’ve suggested here but it’s very difficult to find much written on the subject, although there are lots of wonderful pictures. Smocks were still in evidence at the Great exhibition of 1851 for The Times of 13 June of that year describes how glorious the agricultural workers from Godstone in Surrey looked, the men and boys in their smartest smocks and the women in their best Sunday dresses.

Christening dress in English Smock Embroidery: detail of concentric circles (wheel shapes suggest the trades of carter or wagoner.)

But in truth, by the 1850s, the wearing of the smock was in full decline. As agriculture and transport had become more mechanised the smock became seriously dangerous. At the same time, cheap manufactured clothing increasingly dominated the market. Soon smocks were symbols of the past, seen in Kate Greenaway’s picture books on arcadian little children and worn by old men at home to the horror to the young who returned from their city lives to visit A story from 1937 in the Sussex County Magazine tells of a girl in service in 1887 who returned home with a new coat for her father. The old man cast off his smock but didn’t like the coat and preferred to walk through the village in his shirt sleeves, cold and thoroughly confused longing for his smock but not wanting to shame his daughter. Another story relates how a boy in a house where a young woman was in service asked why her father visited her wearing his nightgown.

Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932) remembered people wearing smocks in Sussex during her youth and she obviously had a soft spot for them as she collected many which are now on display (I think they are on display) in Guildford Museum. In some parts of the country, like Herefordshire , Buckinghamshire and Sussex smocks are documented as being worn into the C20th but such sightings must have been remarkable for their rarity and thus remembered. Now, hand smocking is almost solely reserved for baby clothes and for toddlers’ shirts and dresses – and, of course, for christening dresses. It still seems to me to be one of the prettiest ways of dressing little girls and because of that I don’t think it will ever become a lost craft.Perhaps it was pure perversity on my part that the one thing I didn’t do with the christening dress was hand smocking!

2 Comments

Impressive and interesting as always!

Thank you – yet more lovely comments from you. They are very much appreciated.

3 Trackbacks

[…] is the bonnet to go with the christening dress shown here. After washing it, I couldn’t resist adding more lines of embroidery in between the pin tucks […]

[…] the term ‘smock’, I refer you back to what I wrote (at some length I’m afraid) here . Smocks might have smocking but they often didn’t. Smocking also came to appear on things […]

[…] in the woods. For more about smocks and the significance of the embroidered symbols of trade, see here (towards the end of the […]